“She’s not coming, Jo.” Linda said with great disapproval. It was my fault, of course. It was graduation for Sue and her twin brother, Paul. Sue was my best friend. When I found out her mother, Linda, didn’t want me to go to dinner with them and their father to celebrate, I said I wouldn’t go.

When Sue found out I wasn’t invited to be with the family for the first time ever, she said she wasn’t going either. Linda’s response was to corner me and say, “She’s not coming, Jo,” as if I could make Sue satisfied with my exclusion. It was a tense moment. Somehow, we found a resolution. I said I’d go home to my grandparents and the family went to a fancy dinner. It wasn’t the first time nor the last that Linda blamed me for Sue’s decisions. If I could have made it better, god knows I would have.

Sue and I met the spring of 1974 when we turned out for high school track. We were both in the neighborhood of 5’10” with long legs and quickly became running partners. Sue was a runner. I was along for the ride because my real love was long jump. Sue and I ran the 880 yard race. It was two laps around the track. It was extraordinary to run the race with her. In the last half lap, the world would fall away. Noise would stop with only the wind moving past my ears. Suddenly, I felt I could run flat out forever sprinting the last 100 yards. I learned it’s called a “kick.” I always came in second place to Sue’s first. My first place wins were the long jump. I did high jump because the team needed me. The long jump was all mine.

During one of our first runs, I said we had to go by the public library because I had to get a book of poetry by Robert Frost. A good friend was going to Montana for the summer. There was a poem she liked. I wanted to memorize it and recite it to her when I said goodbye for the summer. Who knows where I get these ideas? Sue was quite taken with the plan. We got the book and became instant friends. I didn’t know then that she wrote poetry. Thereafter, she’d tell people we met because I had to get a book of Robert Frost poetry during our workout.

I was in 10th grade. Sue was in 11th. It was my first year out of junior high away from a significant school counselor. I needed a good friend. It took me another year to figure out I was in love with Sue. I didn’t know anything about being in love. I certainly didn’t know anything about lesbians or if I even knew the word. I had a best friend and that’s all that mattered.

[Picture of Sue and I. 1974]

Soon, I learned Sue was a lifelong Christian Scientist. Her mother was a Christian Science Practitioner. A CS practitioner is a trained person Christian Scientists consult when they’re struggling with a need for a healing either physical, mental, or spiritual. When I first listened to Linda and Sue speak of this belief, this spirituality, I was riveted. Suddenly, I knew I found what I’d been looking for to heal my mental health struggles. This was it!

I became a convert. I joined their family attending Sunday school. Linda was the teacher. I went to Wednesday night services where after the readings from the Bible and Mary Baker Eddy’s book Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures the audience members spontaneously testified to a healing they’d experienced. I was on the path to healing. At 16, I was going to figure out this thing called life.

There’s nothing quite like an eager convert to religious people. Probably, a convert of any stripe to dogmatists. Sue and Linda took me in with arms wide open. I’d lost my parents to abuse, divorce, and madness. I’d been living with my grandparents for 18 months. I wanted a best friend and an engaged parental figure. Linda was happy to oblige until I got caught later in the crossfire between her and Sue’s need to become an independent person. But, that was another year down the road.

I’d spend weekends with them when my grandparents went to their beach house so I could go to church. Granny was supportive but a little scared of Christian Science. She told me she lost a friend to cancer because as a Christian Scientist she refused treatment. Granny didn’t want to lose me that way. I told her I understood. Although how a sixteen year old can really understand anything is beyond me.

I’d sit in Sunday school and try to grasp the idea that our physical beings referred to as “matter” had no reality. We were only spiritual beings. We had only to understand this truth and healing would happen. As a yet unacknowledged sexual abuse survivor, I thought this was a good plan. I didn’t want to feel physical pain or any pain for that matter. What sixteen year old doesn’t want to avoid the pain that life brings?

At the beginning of each Sunday school or church service, we recited the Scientific Statement of Being in unison:

“There is no life, truth, intelligence, nor substance in matter. All is infinite Mind and its infinite manifestation, for God is All-in-all. Spirit is immortal Truth; matter is mortal error. Spirit is the real and eternal; matter is the unreal and temporal. Spirit is God, and man is His image and likeness. Therefore man is not material; he is spiritual.”

On a good day, I can still recite it. I’m much better at reciting the Robert Frost poem. There’s been more calling for that in my life. The Scientific Statement of Being was a kind of prayer. It was a reference to recite when my life was being difficult. Surely this could carry me through.

At 14, I’d spent five months in a mental hospital before going to live with my grandparents. I’d tried being born again—twice—with a resounding thud. I knew if anyone needed healing it was me. Transforming my perception of reality seemed like the perfect mechanism. Nobody was around to explain it was not that different from the altered perceptions in mental illness. I had to figure that out myself. Nobody explained denying reality is just denying reality regardless of the venue.

I still had contact with my mother then. Initially, she was not impressed with Christian Science especially after I told her the Walkers were perfect. Shortly after, she embraced Christian Science to an extreme and sent my younger brother, who was living with her at the time, to my Sunday school. My mother went to a different Christian Science church because she and Linda didn’t like each other. To this day, my mother is fond of Christian Science. In her world, it completely confirmed that my getting hospitalized and everything I said that happened to me was all in my head. It was the perfect scenario for her. It was also yet another way for her to make what I was doing about her and be abusive at the same time.

Linda embraced teaching me. I spent weekends feeling loved and included. She and Sue were always there for me. In my life, I was only called Jo by my sports buddies. Because I met Sue in track, she and her family called me Jo. If I didn’t know someone from sports, I didn’t allow them to call me Jo. In the Walker household, Jo was an endearment in my ears. I belonged.

I injured my right knee running two miles with Sue that first season. I was on crutches for three weeks. My knee would no longer hold me up. Doctors could find nothing wrong with it despite two invasive tests. It was the beginning of intermittent mobility issues with my legs that has plagued me on and off since. I took a trip with the Walkers and their friend, Beverly, to Port Townsend while I was on crutches. During that drive, Sue rubbed my knee. I did not want that trip to end. I felt guilty that her touch felt so good. Sue was nonchalant about it. She said it was a healing touch. I’m not even going to try to explain how that fit with CS.

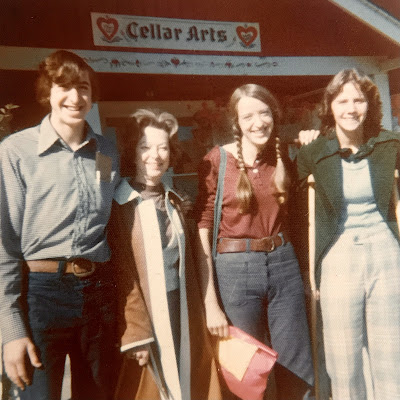

[Picture of Paul, Beverly, Sue, and I. 1974]

Once, I was able to walk again I no longer ran with Sue. I only did the long and high jumps. It was mysterious that I could run three times flat out to do the long jump. Each time, I would limp back up to the start for the next jump. That was all the running I did. It didn’t make sense but neither did much else in life. I dealt with it.

That summer, Karen, my friend in Montana invited me to come visit her in Libby. I would take the train to Whitefish. She would pick me up and drive me to Libby. Linda and Sue made up a bunch of envelopes for the 17 hour trip. I had an envelope to open every few hours. I had my Science and Health and Bible in miniature Sue gave me. I loaded on the train. It was sunny. I remember them pressing the envelopes in my hands, smiling and waving. I had seldom felt so cared for.

It was August 1974. Karen was staying the summer with her parents. Her dad was a staunch Republican and believed President Nixon was blameless, guilty of nothing. He railed at the injustice of those against the president right up until the day Nixon resigned. Their living room was deathly quiet as we gathered around the TV to watch Nixon’s speech. Karen’s dad didn’t have much to say on the subject after that.

Karen, who had been one of my counselors at Western State Hospital, took me around Northern Montana into Glacier National Park and the Canadian farmlands of Alberta in a big loop back to Libby. It was beautiful country. The sky was Montana blue. We camped and hiked. My balky knee was grumpy at times. Karen was not impressed with Christian Science. When my knee buckled at her house, I quickly looked at her. She said, “Yeah, I saw.” I couldn’t “heal” my knee.

Back home, my return was welcomed by the Walkers. Time moved slowly. Everything I did revolved around Sue and Linda. Occasionally, Sue would spend the night with me at my grandparents. We lived in an old fashioned three story building with a gas station and garage in the front. The station was ancient. My bedroom was on the third floor with windows overlooking Puget Sound. The southern view crossed the water to Tacoma, the smelter smokestack, and on a clear day the towers of the Narrows Bridge. The western view looked at Vashon Island and the Olympic Mountains beyond. It was a breathtaking view from the back of an old building from a time when such views were taken for granted. I enjoyed the privacy Sue and I had alone on a Saturday night.

Sue loved horses. Late that summer, she got a horse stabled close by her house on North Hill. I hung out with her while she brushed and cared for the white horse. We road bareback. The only time I’ve been bucked off a horse was when the two of us tried to ride together. The horse didn’t like that. We took turns riding. Galloping a horse is an incredible feeling riding the massive swells of a large body moving through the air. Once, I was running the horse down hill and saw a ditch coming up quick. There was no time to stop. I thought, “Oh shit,” and held on as the horse sailed easily over the gap as I looked down to see us fly.

Sue wrote poetry. I enjoyed her poetry which reflected beauty and movement in a way I could envision. Late in the summer, she was accepted at Centrum, a writer’s camp, at Fort Worden Historical State Park near Port Townsend. Linda and I drove her the two hours to the camp and picked her up at the end of the week. Sue proudly showed us framed poetry she had written in camp. Oddly, her poetry was no longer understandable to me. Her poetry had been taken and reformed into an obscure message only clear to her teachers. Years later she told me it had ruined her writing. (This has kept me from embracing writers' workshops.)

In the fall, Sue got a job as a typesetter for a weekly paper in Federal Way. It was her senior year. She didn’t have a car. I volunteered to drive her to work on Saturday’s. Linda, Paul, or I picked her up.

At school when I had trouble with my right knee, Sue had me put my arm around her shoulders. Other students looked at us funny. Sue didn’t care. I wasn’t about to let a little snickering keep me from putting my arm on her. She just said people were being stupid.

Linda’s best friend was also a CS practitioner. Helen was very active in the church. I thought she was an attractive woman and was drawn to her. Both women’s children spent time together. Holly and Sue were friends who didn’t go to the same school. As Christian Scientists, it was important to have other like minded kids to hang with. Sue patiently answered my CS questions. When I found out she went to the dentist, I asked why. “Teeth need to be cleaned,” she said. However, getting teeth filled was a bit of a dirty little secret.

I got pretty confused about whether masturbation was okay as it was clearly something involving the pleasures of the flesh. I got referred to Helen to discuss my problems. When she found out I struggled with masturbation, she told me to call her when I felt the pull. I couldn’t explain to her that it was an attraction problem. If I wanted to masturbate and thought of calling her, I would feel my attraction to her which would make me want to masturbate which would cause me to need to call her which would trigger my attraction. When I talked to her, it was a great strain to dance around the problem. It seemed the safer course to just masturbate and forgo future calls.

When the question came up with Sue sometime much later, she explained that everyone masturbated and it was a natural physical expression. This further confused me. When is the physical being illusion and when is it to be accepted? I couldn’t understand how these two contradictory states could be reconciled. This is a problem I have with religion in general. A statement of finality requiring belief either is true or untrue. It can’t be both true and untrue. Either god is a loving being or he’s mean and doles out bad things. At the front of the church where the reader spoke on Wednesdays and Sundays, the words “God is Love” were emblazoned in gold letters. Why would god be unloving if he was love?

Linda stopped teaching Sunday school. For the older kids, our new teacher was Phyllis. She was older and had a listening nature with a soft, caring voice. We began to have more robust discussions about the challenges of becoming adults in a non-CS world. I trusted Phyllis. Sunday school no longer caused me to withdraw into myself in an attempt to not be a physical being. Phyllis didn’t require that.

As bad weather came in the fall, Sue met John. I was crazy with jealousy. I played the guitar. John played the guitar many times better. I lived in downtown Des Moines. John lived on North Hill by Sue. John was a boy. I was not. Sue didn’t understand my jealousy. I didn’t either but I felt it. When Sue wasn’t hanging with John or working, she was hanging with me. Linda got short shrift. Her beloved youngest daughter who followed in her CS footsteps didn’t have time for her. To deal with my pain, I returned to spending some weekends with my grandparents at the beach house and skipping Sunday school.

Every lesbian knows the problem with falling in love with straight women is that they are straight. My additional problem being in love with Sue is that I didn’t know I was a lesbian. My feelings were confusing. My mother believed lesbians were better off dead. This left me with a profound distaste for my own romantic inclinations. In the mid-seventies, there were no lesbian/gay awareness or support groups in public schools. Women’s centers were on college campuses. I never heard anyone say a positive thing about gay people.

I remember Sue picking me up from school one day. I felt tortured by her having a boyfriend. She said, “Jo, you have a glass heart. It breaks easily.” I wasn’t sure what a glass heart was but it didn’t sound like a good thing.

Fortunately for me, the track season came around again. Practice was daily. I got to spend time with Sue every day. We bussed to track meets. John wasn’t in track. I was a fair high jumper but a great long jumper. Sue wasn’t a sprinter but a great long distance runner. In those days, girls running 880 yards was considered long distance.

Sue got a light calico kitten she named Harmony. One of the odd things about Christian Science is there is a lot of talk about what’s “good” but no talk about what’s bad. Things that promote CS values and spiritual healing are good. Ideas that don’t promote that are “not good” but never bad. I found this coded thinking confusing. When Harmony was kneading on Sue’s lap, I said, “I don’t think that’s good.” I meant it wasn’t “right” in CS parlance. Sue’s response, “She’s just doing what’s natural to her as a cat.” I looked to Sue to explain the world from a CS perspective. She was patient.

We were allowed to go to my grandparents’ Vashon Island beach house for a couple days during spring break. Linda gave grudging permission. It was my first time alone with a friend at the beach house. Sue and I had time to walk on the beach, sit around the fire, read, and talk. When it was time to go, we couldn’t find Harmony. We called and called, looking everywhere inside and outside. Finally, we were forced to call Linda and Granny to say we couldn’t find the cat and couldn’t leave. I’m not sure Linda believed it.

That night we heard Harmony mewing in her little kitten voice. We tracked her down to behind and inside the back of the couch. She had crawled inside the couch and fallen asleep. We left the next morning grateful we hadn’t left without the cat. Harmony would have died locked up in the house.

In May, disaster struck. The track meet was at a school in the hills east of the Kent valley. Sue and I both did high jump. We were evenly matched. For some reason as I jumped the high jump, I kept landing on the far outside of the landing pit. The pit was a 24” inch thick vinyl covered mattress. Sue told me to be careful. I was jumping first and she followed. On my third jump, I sailed over the bar and completely over the pit, landing on my upper back. It knocked the air out of me. Sound stopped as I lay on the grass waiting to breathe.

Suddenly, Sue and Coach “Mac” McGregor were on both sides of me. Sound came back as I took a breath. “Jo, are you okay?” Sue said.

Mac said, “Just lay here a minute.” I waited a couple minutes. “Okay, try to get up.” As I moved my head forward to get up, tears sprang in my eyes. I was surprised. I couldn’t feel anything but there were tears.

“Oh, you’re hurt,” Mac said. “Just lay still. Don’t try to get up.” Then to someone, “We need to call an ambulance.” I had never been in a ambulance. It came with medics and a board. I was loaded on the gurney and bumped along the field. Someone said they would call my grandmother. They were taking me to Valley General Hospital.

Just before they got me to the ambulance, Linda appeared. She had never been to a track meet. She looked down at me on the gurney with her CS practitioner’s eyes. She said, “You know the truth, Jo. You know, Jo.” I knew what she was saying: There is no life, truth, intelligence, nor substance in matter. All is infinite Mind and its infinite manifestation... Then I was loaded into the ambulance with sirens blaring and rushed to the hospital.

Sue met me there along with my grandparents. I was x-rayed. Initially, they couldn’t find anything. A sharp eyed tech finally saw a line in my vertebrae. I was diagnosed with a compression fracture and kept in the hospital that night. I was alone in a hospital in a single room with nurses for company.

Granny was upset because she thought Linda had gotten the emergency notification before her. I explained that Linda just showed up. Granny was skeptical but all I had was the truth. Linda later explained to me she just “had a feeling.”

I was prescribed Codeine pills for pain. I began to eat less and less because I didn’t feel good. I finally stopped eating completely. I stayed a second night. The next day, a student nurse asked me why I wasn’t eating. I told her I didn’t feel good and my stomach hurt. After consulting with a nurse, they determined I was having a reaction to the Codeine. The student nurse was very kind saying, “It’s best if you let us know what’s going on so we can help.” What a concept? I was used to keeping things to myself.

Sue visited me the second day on her way to work. It was always good to see her. Granny came to visit and talked to the doctor.

The second night my mother came. At first she seemed worried about me. I was trying to follow what she was saying. I didn’t feel good. Then, she started yelling at me. “It’s your fault you don’t live with me. I’m here for you. But, you choose to live with your grandparents.” “You make me worry about you.” “You should treat me better.” She went on and on. Finally, she stalked out and left.

I was upset and started crying. I felt small and alone in that hospital room. I couldn’t believe my mother would yell at me while I was laying in a hospital bed. The student nurse came in and held me. I sobbed. It was typical of my mother to blame me for an imagined hurt I’d caused her. I talked about my mother. I didn’t want to see her in the hospital again. She didn’t return.

(I learned at 21 I could designate a Durable Power of Attorney to make decisions for me if I was medically incapacitated. I drew up the paperwork with an attorney to designate my partner in this role. It’s been current since. I never, ever wanted my mother to be able to stroll into a hospital room and subject me to her decisions about my welfare—ever.)

Sue came to see me on her way to work the third day. I still couldn’t walk without pain and spent another night. The fourth day the doctor said I could go home if I wasn’t active. I pondered this and told him if needed to stay in bed I shouldn’t go home. He said I could be fitted for a back brace the next day. My grandparents talked to the doctor. Linda called me and expressed her disapproval of my staying another night. Christian Science and hospitalizations are incompatible. Linda also said Sue was tired from school, working, and visiting me.

Sue told me she was too tired to come the fourth day. In my mind, she had to come every day. It was how I knew I was important to her. I whined to her. She came to visit but I felt bad. Emotional extortion didn't feel good.

A technician came to fit the back brace. He was in my room alone with me. He said he couldn’t fit it properly with my panties on. I ended up standing naked while he fit and adjusted the brace. I remember the sun streaming in through the shear curtain. I wasn’t able to assert myself at 17. I was extremely thin. I felt humiliated and vulnerable standing there alone with him. Later, I understood it should not have happened that way. At the time, I felt trapped.

I spent one more night. Granny came to get me when I was discharged wearing the uncomfortable back brace. I closed off the experience in my mind. Freed of the medical model, I planned to concentrate on my CS healing.

It was a Thursday when I got back home. Granny and Grandpa went to a Masonic Temple function. Sue came over. I was alone with her and suddenly wanted to got outside and run with her. I could be healed. I knew it. I had delayed it. Now was the time. It was May. The sun hadn’t set. We ran to the cliff above the Des Moines marina. I marveled at the beauty of Puget Sound, the Olympics, and Tacoma to the south. We sat and watched the sun set.

When I got back, my grandparents were already home. It was one of the few times my Grandpa was upset with me. “Where were you? We were worried.” I made some noise about wanting to be outside. I wasn’t going to admit to running.

“Here, you just got out of the hospital. You’re out there. We don’t know where. We were worried.” I apologized. We left it at that.

Going to school, I really tried to make myself wear the back brace. I knew it cost my grandparents $150. It was uncomfortable. It didn’t look good. After a few tries with Granny watching me closely, I gave it up. I felt bad about it for a long time. I remembered that man fitting it with me naked. I couldn’t make it work even if it cost a lot of money. It wasn’t the last unexpected expense I caused my grandparents.

In terms of track, two meets remained of the season. Naturally, I wanted to participate. Having more brains than me, Mac emphatically said, “No!” I did jumping jacks to prove I was okay. She still said no. All that remained in my world was for Sue to graduate high school.

Blaming me for Sue’s lack of interest in her, Linda had been getting less and less patient with me. I was also terribly upset by Sue’s impending graduation. This is what led to Linda’s pronouncement to me, “She’s not coming, Jo,” for the graduation dinner.

[Picture of Paul, Linda, Sue, and dad with dogs, black and white Tokey and Cookie. 1975]

[Picture of graduation party. Sue, me, and Paul in the middle. 1975]

Elyn, Sue’s sister, lived with her husband close by in Burien. The CS church was also in Burien. Sue spent time at Elyn’s. Since I spent time with Sue, I was often also at Elyn’s. Elyn and Dan were also tall. Elyn looked a lot like her family. I was comfortable with Elyn and Dan and spent hours there.

After her graduation, the friction between Sue and Linda increased. I started avoiding Linda. In late June, a local legislator the family knew needed a house sitter on Lake Burien close to Elyn’s for a couple weeks. Linda consented to let Sue stay there alone with one proviso: That I not spend the night there with Sue. I was puzzled by this and asked Sue why.

“They [Linda and Helen] think you’re a bad influence.”

“Why?” I don’t remember exactly what she said but I was hurt by their thinking and didn’t understand.

It didn’t matter what Linda wanted. I still spent the night with Sue at the lake house. Sue was alone. I wanted to be with her. Her mother found reasons to stop by. Elyn’s house wasn’t much further. Linda said she was shopping or visiting Elyn.

One Saturday morning, I got up and moved my car so Linda wouldn’t see it and think she needed to stop. Linda went to the church Saturday mornings so we knew she’d be by. I had been driving my Granny’s 1962 two tone blue and cream Thunderbird. There weren’t that many around. I drove down the street, turned right, and right again to park on an adjacent street and walked back. Not long after, Linda came by to check on Sue. I hung out in another room until she left.

A few minutes later, Linda returned. I didn’t know what to do. The legislator had a home office that was a separate part of the house. The door to the office was locked. Sue unlocked it and put me in there. I heard Linda.

“Sue, I know Jo is here.”

“She’s not here.”

“I know she’s here. Jo, dear, where are you?” Linda walked from room to room. “Jo, dear, I know you’re here. Come out, Jo.” I was frozen. I heard this woman’s voice who I had trusted not too long ago. Here she was calling out to me like Hansel and Gretel’s witch, wandering around the house looking for me. I waited, barely breathing. This woman who had meant so much to me was now calling to me in this insidious way as if I was a criminal.

“Oh, Jo, come out dear. Come out, Jo. I know you’re here.” Sue was incensed. Linda was persistent. After searching each room in the house, she grudgingly left.

As hurt and shaken as I was, Sue felt even more betrayed. I was too focused on my own feelings to ask questions about what was going on for her or listen well. Linda was no longer a woman either of us trusted. I had lost a surrogate mother. Sue had lost her mother. I asked Sue why Linda didn’t check the office. I knew I would have. She said, “She would never check the office. To her, it’s not a part of the house. I knew she wouldn’t go there.” She understood this in a way I couldn’t.

When I left later to get my car, I found a note under the windshield wiper. “Hello dear, I missed you” was all it said with no signature. She had left the house and instead of driving east or west on the main road had gone to a side road for no reason other than to look for my car and found it.

The collapse in trust between Sue and Linda caused Sue to decide to move in with her sister, Elyn, after house sitting. My grandparents had a huge green Ford station wagon. Sue asked me to help her move. Linda was no longer speaking to me. Sue loaded the car. John and Paul helped. I wouldn’t go in the house. I sat quietly in the car and waited to drive Sue to Elyn’s.

Linda stood several feet from the window I had rolled down because the weather was nice. “She’s moving, Jo. She’s leaving. This rests squarely on your shoulders, Jo. I hope they’re broad enough and you can live with it.” After her pronouncement, she just stood there staring at me. I felt she was willing me to collapse, to beg forgiveness, to refuse to help Sue move. I sat there tensely staring straight ahead enduring her disapproval and disappointment. She had moved from a welcome loving shelter to a desperate women willing to blame her daughter’s independence on me. I had no words to even frame a response in my mind let alone a response to her. I vowed to not tell Sue what she said to me. Sue didn’t need it either.

It was at Elyn’s that Sue reconnected with Eric, a long time family friend. Sue told me Eric’s car had been hit by a fire truck speeding to an emergency through a Burien intersection. Eric sustained a head injury causing him to be unable to work. His ability to communicate was simplified. Sue was drawn to him. John lost Sue’s interest. It was a good news, bad news situation for me.

We were still going to church and Sunday school. I avoided Linda. There was an opportunity to go to a CS camp for older kids in Banff, Alberta, over the Labor Day weekend. Sue, Holly, and I signed up. It was a 17 hour chartered bus ride from Seattle to Banff filled with end stage teenagers. I sat next to Sue. Banff was incredibly beautiful from the historic Banff Springs Hotel to the endless evergreen covered mountains. I had never seen a place so enchantingly European.

We stayed in college campus dorms. The three of us were in a dorm with two other girls. Sue and I were in sleeping bags on the floor. One night there was a spirited conversation about sex before marriage. The other two girls insisted if a girl had sex before marriage she would feel dirty and disgusted with herself. Sue and Holly said that wasn’t true in a way that left little doubt of their first hand experience. In the silent middle, I started to feel a loss about Sue that dipped into a sea of emotional pain. I hadn’t felt this bad in a long time. I took a walk. I stepped outside and began to sob.

I had nowhere to go. I got off the path and found a bush to crouch beside as I poured my heart out in tears, cries, and agony. I couldn’t do it quietly. The darkness was a blanket. A few times I heard people nearby. “What is that?” “I think someone is crying.”

“Yeah,” I thought, “someone IS crying.” No one came to check on me to ask if I was okay. “Damn, Christian Scientists, they can’t even check on me.” At the same time, I didn’t want anyone to see me or ask questions. I didn’t know how long I was out there. Once I was able to stop crying, I made my way back to the room and my sleeping bag. I was distraught. I hadn’t cut myself for well over a year. Now all I could think of was going into the bathroom, breaking a glass, and cutting myself. As I replayed this vision in my mind, I started to shake. It wasn’t just a trembling like I was cold. I was a convulsive movement from my stomach I couldn’t control.

“Jo, are you all right?” Sue asked.

“I...can’t...stop...shaking.” My words came out broken between jerks of my muscles.

“What do you need?”

“I...don’t...know. This...hasn’t...happened...before.” I couldn’t very well tell Sue that I wanted to hurt myself. It would mark me instantly as a crazy person. We waited. The shaking would start to subside and return just as disturbed.

“What’s going on with her?” one of the other girls asked. Sue said something about me being in Western. I wasn’t listening.

After awhile Sue said, “I think we should call Helen.” As she was Holly’s mother, I really didn’t think that was a good idea but Holly piled on. They didn’t know that them talking about sex triggered my pain about Sue.

“I...can’t...walk.”

“We’ll help you. There’s a pay phone down the hall.”

“No...”

“Come on.” Sue and Holly half carried me, half dragged me to the phone. Sue put through the call explaining to Helen I was having trouble.

“What’s going on, Jo?” Helen’s soothing voice asked.

How in the hell was I to dance around this? I was too distraught to think my way out of a paper bag. Sue listened as I worked my way to saying I was upset about hearing people talk about having sex.

Helen’s voice sharpened, “Jo, who was talking about having sex?”

“People...in...my...room.”

“WHO was talking about having sex, Jo?”

I tried to avoid answering but finally said, “Sue...and...Holly.”

Sue threw up her arms saying, “I can’t listen to this,” and walked away. Anyway I turned, I seemed to be failing. I got off the phone with Helen eventually. I don’t know what she said but the damage was done. I’d outed Sue and Holly. Sue helped me back to the room. She’d told Holly what I was saying to her mother.

I don’t remember anything else that weekend except the bus ride home. I was okay and then the shaking would start again. Sue was attentive. I couldn’t control it. It came in waves. I would look at Sue with sad eyes as it started up again. Seventeen hours is a long trip in pain.

The next thing Sue did was start volunteering at Channel, a crisis line and drop in, center in Des Moines. She took the crisis line answering training. I also took it. George, a long time volunteer, taught the class. George was twenty years older, divorced, with a couple kids. He was a mechanic for a Toyota car dealership in Puyallup. He had craggy looks and a smoker’s voice. He seemed to have gotten his life together.

Channel was a magnet for troubled people trying to do good for other troubled people. The evening training was over several days. I realized during the training that I couldn’t possibly answer the crisis line. I appreciated learning about “active listening.” But, I did not have things together. I had been a crisis line consumer since I was 12. I opted out of further training. However, Sue took to it. George mentored her. Soon, Sue and George were doing shifts together. This didn’t bode well for me. (Never fall in love with a straight woman. It doesn’t go well.)

Sue started talking to me about George. How much she liked him. What a good person he was. My internal jealousy flamed. Any work I’d done to hide my suicidal thoughts or wanting to hurt myself was gone. What was worse, I called Sue during her shift at Channel because I was in crisis. (I hadn’t been taught anything about good boundaries.) After a few phone calls, Sue was smart enough to refer me to a coworker. Unfortunately, the coworker’s mother knew my mother. I told her about being suicidal but didn’t feel safe revealing my feelings about Sue and George. I didn’t have a therapist to talk about this incestuous situation who could help me with out of control feelings. This wasn’t covered in Channel’s active listening training.

My bad behavior culminated in calling Sue at Channel to tell her I had cut my wrist.

“I’m going to call your grandparents.”

“Go ahead. I won’t be here.”

The problem was I didn’t really want to kill myself. Cutting my wrist caused a certain amount of risk. To hedge my bet, I wanted someone on the receiving end to catch me. Sue was that someone. I hadn’t actually cut my wrist when I called Sue.

It was late when I hung up the phone. My grandparents were asleep. I grabbed a red towel out of the bathroom so the blood wouldn’t show. I already had razor blades. I drove to the Safeway store parking lot two blocks from Channel. I cut my wrist deeply, accidentally missing the artery, wrapped it in the towel, and drove to Channel.

George and Sue were there when I walked in, worried it took me so long. George saw the red towel and feared it was soaked in blood. When he unwrapped it, he said I would have to go to the hospital. Sue called my grandmother after hanging up with me. In calling Granny a second time, they agreed Sue would drive me to the hospital and they would meet us there.

The cut required 14 stitches. I was shaking again. A nurse said to me, “If this doesn’t kill you, that will.”

“That what?” I asked.

“The drugs you’re taking.”

“I’m not taking any drugs.” Once she realized my problem was mental health rather than addiction, her attitude toward me softened. She was much kinder. I knew this was wrong but guiltily accepted the better treatment.

There were more hurdles. A sheriff’s deputy came in to ask questions. I understood it was illegal to kill myself. I have a clearer picture of what was going on now. Sue stood in the room. I didn’t want to get hospitalized. (I’ve since learned the value of hospitalization.) I patiently explained I never intended to kill myself. He looked at me and shook his head.

After he left, I asked Sue how she was. “I feel used.” I couldn’t argue with that. She was absolutely right. I was ashamed. I shut up. My grandparents let me spend the night on a couch at Channel. Sue sat by me.

When I went home the next day, Grandpa had tears in his eyes. “Honey, the idea that you could...” and he choked up. I’d never seen my Grandpa cry before. I hated to be the cause of it. Granny called Highline-West Seattle Mental Health Center. (We had community mental health centers then before Ronald Reagan discontinued the social safety net.) I got an appointment that day with a counselor named Trish.

I don’t remember who took me to the appointment with Trish. What I do remember is that Trish recommended I go to a hospital. I know my grandparents took me to the psychiatric ward at the University of Washington Hospital in Seattle. It was on the fifth floor. I remember looking down at the city from my room that night and thinking, “So, this is what being hospitalized again feels like.” I was hoping to never return to the psych ward. I failed.

Being hospitalized usually includes an assessment process. I remember taking the MMPI (Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory) again. It didn’t matter I’d taken it three years earlier. It had over 500 questions, many of which are similar, phrased in different ways as if I’m too dumb to know I’m being repeatedly asked the same questions. It took two hours.

It was November just before Thanksgiving. I was 17 until the end of December. I was told I would have been involuntarily committed had I been 18. It felt too close. Involuntary commitment was something to be avoided.

The most profound experience was talking to a male staff person the second evening. I remember him with red hair and beard. He asked me to tell him what was going. After struggling to speak, using short, staccato phrases, I was able to tell him I was jealous of Sue’s boyfriend, ashamed of it, and wanted to kill myself. The conversation led him to say something I’d never imagined possible, “You know, it’s okay to be gay.”

I did a double take. “What? You’re saying it’s okay to be gay?” I couldn’t believe it. I had to make him repeat it several times. My ears couldn’t process what I was hearing. He also intimated telling a 17 year old this could jeopardize his job. In those days, I’m sure it could. I’m grateful he took the risk.

My grandparents came to family therapy. It was hard. I made myself say to them, “I’m afraid I might be gay... They told me if I am it’s okay.” I looked at Grandpa waiting for him to dispute it. They both nodded. I still couldn’t believe it applied to me.

Granny wanted me to come home. Of course, I was missing Sue. On the third day, I went home. Because I was admitted without my family doctor’s order, I later learned my grandparents’ insurance wouldn’t cover the cost and they were on the hook for $150 a day. (I’m not sure how that could be as they weren’t my legal guardians.) I was relieved I’d only been there three days. I didn’t want to think of the bill if I’d been there longer. I hated costing my grandparents more to support me when my employed father paid nothing.

Before my discharge, hospital staff referred me to the Women’s Center at UW to get more information about lesbians. I didn’t know if I could do that but it was an option. Although I told my grandparents I might be gay in the safe confines of the hospital, I promptly forgot it when I was released. I told no one. I couldn’t even bring it up to myself. I continued to feel unrelentingly suicidal.

Sue tried her best to support me. A few nights later, she was driving me around in my grandmother’s Thunderbird along Redondo Beach near Federal Way. I was having a really hard time. All I could feel was wanting to be dead. At her wit’s end, she said, “Jo, just tell me what’s going on.”

“I don’t know. I don’t know what’s wrong.”

“Just ask yourself what it is. Notice the first thing that pops in your mind.”

I wanted to know. I didn’t want to know. Dare I do this? Listen to the first thing that pops into my mind? “Okay,” I said. I took a deep breath. I said to myself, “Okay, what is it? The first thing that pops into my mind. That’s it.” I waited. The sentence quickly came to me, “I’m a...lesbian.” I heard a loud buzzing in my ears like a freight train. I nearly choked. “Oh, god, no,” I thought. “Anything but that.” I still believed being gay was worse than being dead. “No, no, no. It can’t be.” I kept hearing that terrible sentence repeating in my mind. “I’m a lesbian.” It was the worse possible truth. I thought my head would explode.

Sue asked me what it was. I didn’t know how to tell her. I didn’t want to tell her. I wanted so bad for it to not be true. “Okay. I’ll tell you. But, you have to tell me right away if you hate me so I can jump out of the car. Promise? You’ll just tell me if you hate me?”

“I promise.”

“Okay. I’m not sure. I’m hoping it isn’t true. I don’t think it could be true. It couldn’t be, but I might be a... lesbian.” I told her and held my breath.

Sue had the most perfect response. “So?”

All that churning inside of me. All that self hatred came down to one word: So. “Do you hate me?”

“No. Why would I hate you? I’ve known you loved women. It’s okay. It’s not a bad thing. It doesn’t matter to me if you are a lesbian.” I was stunned. I had told my best friend this secret so awful I’d rather die than have it be true, and she said, “So.”

After talking to Sue, I told Granny I wanted to go to the UW Women’s Center to talk to a lesbian. I called and made an appointment. I was terrified. I drove into Seattle to the University District, found the building, and parked. It was a unassuming building on University Way. I was so nervous I was shaking inside. I climbed the stairs. I met with a woman who I’m sure had a name but I only knew as a LESBIAN! I have no idea what we talked about. It’s funny to think about now after being a lesbian for 45 years.

Driving home, all I could think of was I wasn’t interested. I wanted to get as far away as possible from lesbianism. When I got home, Granny asked me how it was. “It’s not for me,” I said. She nodded. It wasn’t in approval or disapproval. It was just an acknowledgment.

After that, I launched myself into a heterosexual frenzy. I'd been waiting for the feminine fairy to sprinkle her dust on me so I would become feminine. I’d waited through junior high and into high school. Other girls were feminine, carrying purses, and wearing makeup apparently without difficulty. I just needed to get on board.

I got my ears pierced, wore short dresses, and forced myself to carry (gulp) a purse. I was ready to date boys. I dressed that way to go to church Sunday hoping to make a splash, possibly running into Linda. I saw Linda. I was trying to prove I was reformed. She wasn't impressed. I asked a guy to the Sadie Hawkins dance. We went. I don’t remember his name.

Sue continued to work as a typesetter and moved in with Christie, the Channel manager, by Star Lake near Federal Way. Gary was a guy I met at Channel. He invited me to the drive-in to see two Billy Jack movies. The first movie was quite violent and upsetting. The second started with a gang rape scene. We left to go to Sue’s birthday party at Christie’s. I went into Sue’s bedroom, laid on her bed, and started violently shaking.

I heard Sue angrily say to Gary, “What did you do to her?”

Gary held out his hands, “I took her to a movie.” Personally, I thought it a very poor choice in movie.

I tried to spend time with John. He hooked me up with his friend, Dave, a very smart, tall guy for the Homecoming Dance. It didn’t take. Now, Dave is a fine man with a lovely husband.

There was a semi-creepy guy interested in me at Channel. I don’t even remember his name. He asked me to go to Salt Water State Park with him. We walked and talked. He didn’t have a car so I drove. We held hands. He was physically comforting.

One evening he said, “There were three women I noticed at Channel.” He listed two. “You were the third. When you went out with me, I thought you would do.” I should have stopped him then with his dismissive attitude saying I was third best. I didn’t.

We started kissing. I had picked him up at his house where he lived with his mother. He was in his early twenties. I wasn’t attracted to him but his touch felt good. I had fun making out. I’d never made out before.

On our third date, we spent time in the evening together kissing and touching. My grandparents were asleep when we got there. We stroked and kissed. He asked me if he could give me a massage. I laid on the couch on my stomach. After massaging me, he laid down on top of me. I could feel his penis pulsing against my back. We were one door and twenty feet from my sleeping grandparents. It was late.

He said, “I was wondering if you’d like to have sex with me.” It was as if he’d thrown a cold bucket of ice water on me. Any physical feelings I had toward him vanished.

“I don’t think so,” I said. Shortly after, I drove him home. We made obligatory noises about continuing to be friends. I knew it was over. He’d just wanted to get laid. I’d proved to myself I could have sex with a man if I wanted. I was done...onto the next chapter.

Meanwhile, the relationship between Sue and George continued to expand. Sue moved in with George at his house near Angle Lake by SeaTac Airport. George’s kids were older. He had a protective and scary Doberman Pincer. Sue quit her hated typesetting job. She went to work in the parts section of the Toyota dealership in Puyallup where George worked as a mechanic.

I visited her a few times at George’s house. She pretended all was good. The dog scared me. She insisted the dog was safe. I didn’t believe it and believed it even less after the dog ripped a long tear in George’s forearm. The daily interactions fell away. I called her one last time at work. I told her I missed her. Sue responded, “Why?” Yes, indeed, why? It was over. Our emotional relationship was over. I knew and stopped calling her. I waited for her to call me. She did finally announcing that she and George were getting married. It was a justice of the peace wedding. I wasn’t there.

With Sue out of my life and me proving to myself I could sleep with men if I wanted, I found a girlfriend from junior high who expressed interest in seeing if we could sleep together. Sandy and I had discussed it in the fall. I called her up in January and said I was interested. We started doing things together getting more emotionally attached. We decided during the last week in February that we would spend the night together Friday. We referred to it as The Week We Waited.

One of the brilliant things about being a lesbian in those days was girlfriend sleepovers. They happened all the time. My grandparents couldn’t really inquire because we’d have to broach the Are-You-a-Lesbian question so it wasn’t asked. Finally Friday came around and we were in my bedroom at the station. The moon was shining in as we stood by the window. The moon shined on Sandy’s face as she looked up at me. As I bent my head to kiss her for the first time, I thought, “Oh my god, I’m kissing a woman!” As our lips touched, it changed to, “Oh my god, yes, I’m kissing a woman...”

Sandy was my first sexual relationship. Sue was not forgotten but was put on the back burner as I threw myself into the passion of being sexual. As I finished high school, my contact with Sue was much less frequent as I followed her life in our brief interactions over the years. Her life wasn’t kind to her or even decent from what she told me.

My next visit with Sue was later in the year. She visited me at Vashon with her newly adopted dog, Conda. We had a great visit playing on the beach in the sand. She ran with her dog. She was beginning dog training with Conda. She was relaxed and seemed more like herself. I don’t remember if she stayed overnight. I was sorry to see her go.

[Pictures: Sue with Conda. Me playing in the sand. 1976 ]

I moved with Sandy to Philadelphia for her first year at the University of Pennsylvania. While there, I received a letter from the church politely but firmly stating it would be best to remove my membership. It was just as well. It was clear to me that any god who would discount my lesbian love was not a god I wanted to know. I knew my love could not be wrong. Love is love. We moved back to Des Moines the following spring.

Sue wasn’t good at staying in touch. She moved often. When she wrote, I’d write her back but she’d never respond. I’d just wait until she contacted me again. She would visit in my dreams. She’d show up in a dream. I’d say, “Sue, I’m so glad to see you!” We’d have a good talk in the dream. It was how my heart kept in touch. I couldn’t chase her. I had a stable job and living situation. She knew how to get in touch with me. A couple times she’d drop by the station visiting her mother and leave a message for me.

She divorced George. She told me he raped her. I hadn’t liked George for a long time. I wasn’t surprised he could be violent and assault her. She told me another man raped her. She disappeared for awhile. I had a feeling something was up. She’d gotten pregnant from the rape. She’d gone away to have a son and relinquished him for adoption. She’d stipulated the baby go to a Christian Science family. Unfortunately, the CS community was so small she heard which couple welcomed the adoption of a baby boy. Sue told me all this in a visit from Alaska where she was living on a drive to the ocean.

At the ocean beach, she was relaxed. She was driving her Isuzu Trooper II she’d driven from Alaska. We ended up leaving our coats on the beach when we walked. She chided me for being worried when she left her car keys under the coats as if to say, “Trust in the power of good.” I had trouble enjoying the walk while considering the disaster of being stuck on the beach unable to access a locked car far from any phone. Had I been more assertive I would have just taken the damn keys and put them in my pocket, power of good be damned.

Sue decided to become a Christian Science Nurse. It seems like an oxymoron. However, it involved nursing training in Boston at a Christian Science hospital. It’s where one goes when the healing ain’t happening on schedule. I’m sure this made Linda happy. Sue disappeared again.

I next learned that Linda had breast cancer and Sue had put her CS nursing to good use. She said it was hard caring for her mother later when she told me Linda had passed away. Sue had finally gotten to have a relationship with her father after Linda died. Her father literally never spoke when I was around him unless asked a direct question. His answers were brief. He had never been a serious member of the church. He and Linda had led very separate lives. Sue was relieved to spend good time with him.

Ultimately, CS nursing in Boston hadn’t worked for her. Sue was unable to deny physical comfort to those in the CS hospital such as holding a patient’s hand, giving a massage, or giving a hug. She had conflict with CS staff over this and quit. “God is Love”...

Sue visited Phyllis, our former Sunday school teacher, and told me she had quit the church. I was surprised and delighted because Phyllis had been a lifelong member. Sue gave me her number. I went to visit for dinner one evening. By this time, I had moved to Olympia with my second partner, Elizabeth, another high school friend.

I’m sorry to say I wasn’t as thoughtful as I would have liked visiting Phyllis. I asked about her leaving the church and Linda’s death. She said the church membership had stopped being loving. She needed to leave. I was young with political ideals and sucked the life out of the visit in an effort to prove I was well. I failed to show enough care for Phyllis’ needs. At ten, she told me it was time for me to go. I realized I’d been inattentive. It didn’t feel good. I wish I’d contacted Phyllis again but life was busy.

Other than the occasional letter, I didn’t see Sue for a long time. Finally, she visited Ronnie and I at our house on the westside of Olympia with her woman lover. Her partner was surprisingly older but seemed kind. Sue, whose hair had always been long, had short hair. She sat alone with me to tell me about her life.

She’d married an African American man. He became violent and used drugs. She’d gotten pregnant before she left him. She told me she was running from him, pregnant, across a park to a hospital. He’d caught her by the hair and pulled her down. She swore she would never have long hair again. She had a son she was raising. I told her about how I saw her in my dreams occasionally. She said, “I have that same dream.” I wasn’t surprised.

She asked me, “Did I used to have a hump on my back?”

I looked at her gaging my reply. “Yes,” I said.

She turned around, “It’s gone now.”

“Yes. It is.”

Sue was going by Susan and struggled to call me Joceile. She finally asked, “Can I just call you Jo?”

“Oh yes,” I said. “And, can I just call you Sue?” The deal was struck. It was so good to see her as always. Then, she was gone again. Her letters were infrequent.

I knew she and her son lived a bit with Elyn and Dan in Alaska. The last time I heard from her, she called me at Vashon. By this time, her son was a teenager. She was upset. It was hard to know exactly what was going on. Her son was being violent. I don’t know that I was helpful. I implored her to set limits with him about safety. I’d been working on my own self care and of my own responsibility to others around self harm. I was pretty firm with her about the importance of establishing safe boundaries with her son. When we ended the call, I didn’t feel like I’d gotten through to her.

I hadn’t heard from her in another year or two when I got a call from Elyn. Sue had also gotten breast cancer. She’d sought a last ditch treatment in Mexico. When the treatment didn’t work, the facility drove her across the border and dumped her. She died in a San Diego hospital a couple days later.

Since that time, Elyn moved back to Washington with Dan and their cats to enjoy retirement. Sue’s twin brother, Paul, came out joyfully according to Elyn. He was successful in business living in Las Vegas with his husband. He also died of cancer in the late 90s.

My last brush with CS was with an older couple who owned a bed and breakfast in Hawaii. The woman was drawn to me for inexplicable reasons. I learned she was a Christian Scientist and made the mistake of admitting my time in CS. She became riveted and had the look of Linda whenever she saw me as if to say, “You know the truth.” She actually said I should return to the church. Lesson learned. Never admit former membership to the religiously fervent.

In writing this, I realized there were questions I’d never asked about Linda, Elyn, and Sue’s life. I wrote to Elyn and talked to her yesterday to fill in some of the gaps about her life, her family, and what happened to Sue. I didn’t know the half of it. I knew only a small slice of their lives. Linda’s religious extremism hurt her family and others deeply including Elyn.

Elyn has accepted her parents did what they thought was right. I talked to her about her parents. I said, “I was there all the time. Your dad never spoke.”

“I know. Whenever I’d come and go at the house, you were always there. It was always mom, dad, Paul, Sue, and Jo.”

“I guess I was looking for a family.”

“I’m sorry you found such a poor one.”

I can hear the specialness in Elyn’s voice when she says, “Jo.” “You know I never let anyone call me Jo after that except my basketball buddies. I’ve never let anyone.”

“Do you want me not to call you Jo now?”

“No. I like to hear you call me Jo. It feels good. It reminds me of that time.” I told her about Sue visiting so much later, asking if she could just call me Jo. I remember our relief of calling each other by our proper names, Jo and Sue.

“I remember she wanted to be called Susan for awhile... You know no matter what, you were special. Whenever she said Jo, there was warmth.”

Elyn told me the ashes of both her parents, Paul, and Sue were sprinkled on Puget Sound. She likes her view of the water knowing they are all there. This answered another question I had about Sue. I now know where to find her last remains. Given my love for the sound, it’s perfect.

I’m upset now and I know why. In talking to Elyn, I filled in those blanks of Sue’s life and death. There were two husbands after George. I also learned she was living in Tacoma for two separate periods finally buying a house on her own, fixing it, and trying to settle there with a good job before getting cancer. She met her son’s father there. Elyn has lost track of her nephew. I think he most likely resides in Tacoma. Sue didn’t call me. I’d have visited her in a heart beat. She knew where I was. She didn’t contact me for her own reasons. And now I know she was just as wounded and unable to heal emotionally as I. So, I thrive for both of us. She couldn’t be still. She couldn’t find her place and just live well. When she called me at Vashon that last time, she was likely calling from Tacoma, not Anchorage, and never told me. It’s painful.

When we delve into the lives of dead people, we must accept what we find. There is no possibility of resolution with them, no chance for discussion or reconciliation. I come up with slanted facts, vague remembrances of things I cannot verify but must simply let coexist. Sue is not here to clarify or expound on her perspective. I took on this static truth when I started looking at what happened. I can’t change the past. I have to live with it, loving Sue with her limitations, as well as, myself with my limitations in each period of my life.

I can see in my mind a clear picture of Sue running in those ridiculous track uniforms we wore. She loved to run. She was good at it. I see her body, her pumping thighs, her strong breathing, running for the shear joy of it. She’s alive in my mind and still shows up in my dreams. Not too often. Just enough to be special.

To my 16, 17, and 18 year old lesbian self who thought, “If you can’t live with the one you love, love the one you’re with,” I love you. I can hold you with your long, thin but resilient body, wrap my thicker arms around you, and say, “I got you.” And for Sue, I can also wrap my arms around her and say, “I got you too. I’m so sorry for how you were hurt. I know you are one with the earth now. The earth is richer for having you as am I.”

L’Chaim.

Joceile

3.10.21

[Picture: Sue and I in Yakima at my father’s apartment in 1975.]